“We need more cops on the beat”

“Access control issues are by far the most significant challenge in API security,” said Erez Yalon, vice president of security research at Checkmarx, and API Security Project Leader at the Open Worldwide Application Security Project (OWASP), an open-source-focused foundation. Four of OWASP’s top 10 API security risks relate to authorization and authentication, Yalon noted. “This is no different, and sometimes even worse, for IoT and smart home appliances.”

Mark Ostrowski, head of engineering at Check Point Software, noted that appliance vendors, working with open source operating systems, can design, build, and ship devices that have vulnerabilities by the time they arrive in a customer’s home. Patching and updating those systems is often difficult, and typically left to the customer to initiate. “The increase in IoT security needs to be adopted in the home as we become more reliant on smart devices.”

Unauthorized access through a product’s app or smart features is something researchers at Consumer Reports have seen, “but rarely,” according to a representative there. It’s typically the domain of “startups or smaller white-label brands” seeking to have a seemingly high-tech product on the market, but without robust quality assurance for testing implementations.

There are privacy laws in 17 states (with Maryland just added) that demand companies safeguard buyers’ personal information. The Federal Trade Commission and state attorneys general also have existing consumer protection laws to enforce security. Consumer Reports forwarded its findings about the Glow pregnancy app’s lax security to the California Attorney General’s office, which obtained a settlement in late 2020. And the FCC’s proposed Cyber Trust Mark could further incentivize companies to keep with best security practices.

“But in general, we need more cops on the beat and greater consequences for companies when they break the law by using weak security protocols,” Consumer Reports researchers said through a spokesperson.

The problem with better-than-official smart home tools

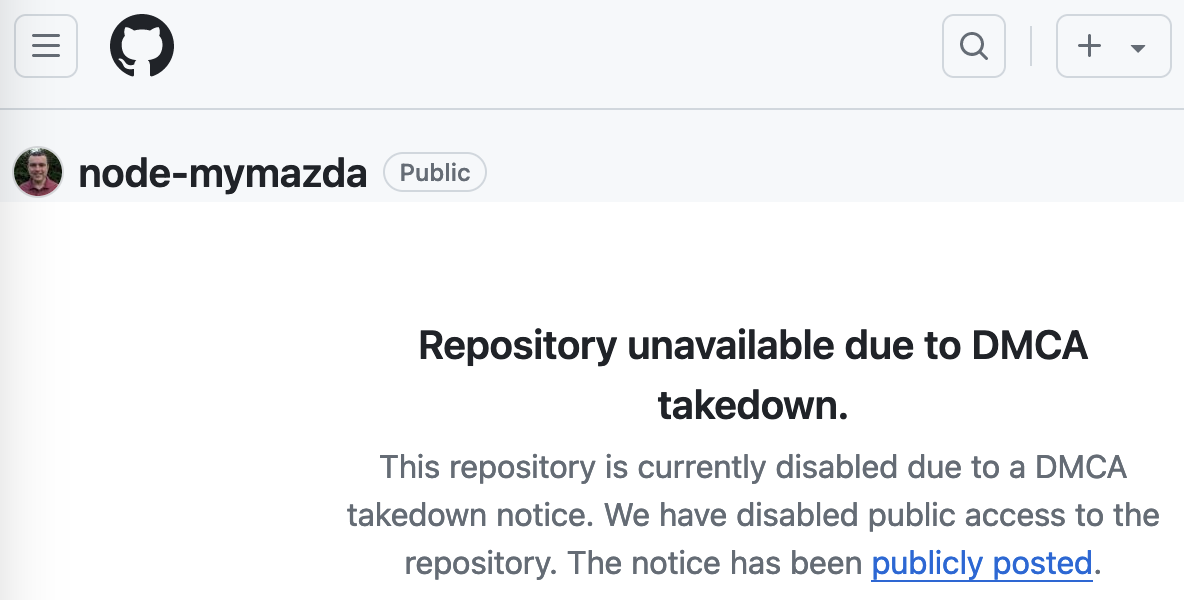

I told Barbour, Dulitz, and Clark I was hesitant to share their story on a news site. They had made something supremely useful for a subset of people who were dealing with “smart” devices tied to not-entirely-smart phone apps. The potential rewards for their work had always been self-satisfaction, a few tip-jar-sized donations, and maybe some nice emails. The potential risks could now involve DMCA notices, threats of legal action, having their code taken down, or some combination of these.

Garage door opener conglomerate Chamberlain last year made a point of decrying “unauthorized usage” of its openers’ API by third-party apps like Home Assistant, after it deliberately sabotaged the related extension. Paulus Schoutsen, founder of Home Assistant, wrote at Home Assistant’s blog that Chamberlain demanded payments from “authorized partners” to integrate with its myQ openers, which the open source, not-for-profit project could not offer. Owners could work around the block with a little ratgdo device and some wiring to restore access to their own devices.

This post was originally published on the 3rd party site mentioned in the title of this this site